Navigating a New Geopolitical Order

Watch my Interview with the Wall Street Journal where I discuss the new geopolitical order.

A Q+A with Former Secretary of Defense Dr. Mark Esper By Barratt Dewey November 24, 2025 Dr. Mark Esper has spent a whole heck of a lot of time in the defense ecosystem. After a decade in uniform in the US Army, he worked as a congressional staffer, a senior policy aide to Sens. Chuck Hagel and Bill Frist, and a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense in the early 2000s. Then, he transitioned into the private sector, serving as Raytheon’s VP for Government Relations from 2010 to 2017. But that wasn’t the end of his military career. Esper was appointed Secretary of the Army in 2017, where he launched the service’s six-priority modernization drive, stood up Army Futures Command, and kick-started many of the defense innovation initiatives we all know and love. He wasn’t done there. Esper was named Secretary of Defense by President Trump in 2019, where he oversaw record RDT&E investments, charted new acquisition pathways, and focused on the ethical implementation of AI within the DoD. He served in that role until 2020, when he once again moved into the private sector. He is now the chairman of Red Cell Partners’ National Security Practice and a Managing Partner at the firm. Tectonic sat down with Dr. Esper to chat about how the defense innovation ecosystem has changed since his time in office, where the biggest risks and threats are, and where he hopes the industry goes from here. Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Tectonic: What are some of the things Pentagon leadership is doing right right now, and what are some things they’re doing wrong? What do you think still needs to change in the Pentagon to encourage defense innovation and bring non-traditional companies through the door? I really like the energy that’s coming out of Washington, out of the Pentagon, and out of Silicon Valley. I use Silicon Valley as a proxy for all the various innovation hubs around the country. I like the energy I’m seeing from VCs and other non-traditional players as well. Private companies that are not VCs and that are more mature, I like the sense of mission, and they want to help DoD innovate. The collective view is a key to our success. Not the only key, but a key to success is going to be technology that gives our warfighters an unfair advantage on the modern battlefield in all domains—air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace. I really like the energy that’s out there. I think it’s critical to sustain it. I hope that DoD and Congress can make the necessary changes and reforms to capture that wind, so that members of the venture community don’t get frustrated and walk away from us. What they can bring to us in terms of technology is just too critical. As Secretary of the Army, you pioneered some of the major innovation initiatives that we see today, especially the Army Futures Command. How do you think that’s evolved since you established it in 2018? During my tenure, the team and I brought forward a number of reforms across the sector, including basic training, collective training, and acquisition. If we want to talk about Night Court and the innovative side, there were a number of things, and Futures Command was part of that. Another part of that was the establishment of cross-functional teams associated with them. I set up the AI Center at Carnegie Mellon University and Futures Command. Now it’s in a new iteration, having been around for five or six years. I think it started off really strong. We had 32 top priorities. And I think by 2024, 23 of them were either implemented or in some operational testing stage, test operational testing, or Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP) stage. It’s come a long way. Some of the authorities were taken away from the last administration, but with this new formulation—and I’ve talked to leaders in the Army—I think Futures Command is going to be even better positioned and organized to capitalize on what they’ve mastered down there in Austin, so I feel positive about the future of Futures Command in this new iteration. After your time in leadership, especially at Red Cell, is there anything you’ve been disappointed by in the innovation space? Reforms never happened as quickly as you would want them to, whether before I was in office, during my time in office, or after I left office. You want to see things move more quickly than they are. And so I would say, again, the very positive development has been the 180-degree turn in Silicon Valley that the venture community has taken toward defense writ large. But again, the disappointment is always in moving faster in terms of capitalizing on the new attitude from the venture side, and making sure that we work closely with them to bring them into the DoD acquisition system, capitalize on what they bring to testing and prototyping, and then, of course, deploy these technologies so we can have this decisive advantage against the Chinese and other adversaries going forward. Before returning to public service in the first Trump administration, you worked at Raytheon for several years. How did your experience at a major defense prime inform your modernization priorities as Secretary of the Army, Secretary of Defense, and then in the private sector with Red Cell? I like to say that my experience was built far beyond just Raytheon. Raytheon was part of that, but I served 10 years on active duty, using a variety of Army weapons systems and working with other services during that tenure. And then I went to DC and worked on these issues on Capitol Hill and at the Aerospace Industries Association. On the technology front, I have a general engineering degree, and Raytheon helped round that out more by focusing on what signals the DoD sends and what motivates, incentivizes, or disincentivizes industry. What is the realm of the possible when it comes to technology? All those shaped my views. When I came into office, my recollection was, here we were, 30-some years after I graduated from West Point in 1986, and we were still using the top weapon systems of the Reagan era when I was at West Point—the M1 tank, the Apache helicopter, the Black Hawk, the Bradley, and the Patriot air defense missile system. While these systems have obviously been upgraded over the years, we needed to move beyond so-called legacy and think about the next generation of vehicles, because we had the technology to make things lighter, more lethal, more survivable, more mobile, both strategically and tactically on the battlefield. The poster child at the time, and still is, was the Bradley fighting vehicle, which is a great system. I think Ukrainians would vouch for it on the battlefield against Russian mechanized platforms. But still, we can do better. We can do better with a future fighting vehicle that addresses all those things, and we showed it when we rolled out our six priorities. One of the things I learned from industry was to pick a set of priorities and stick with them. Don’t change the signal, or it will confuse the industry. They can’t react to recapitalize, retool, hire workers, or make their own investments. We picked those six priorities, and I believe they’re still in effect today. It was long-range fire, soldier lethality, air defense, etc. Some of those, like long-range fires and air defense, proved absolutely spot-on during the war in Ukraine. Those are the two biggest things that we talk about. So I think those things have led to systems such as 360-degree radar, battlefield air defense radar, and upgraded air defense systems to enhance soldier lethality. And you can kind of go down the list of things that are out there. All those things are playing out, and I think that’s the leap forward we’re talking about. It’s not just about the team. I was pleased to see that the last administration continued those priorities, and I think this administration is continuing them as well, which bodes well for the United States Army and its soldiers. I was gonna ask about those priorities. A lot has changed since then, but a lot, as you said, has been proven right. Is there anything you’d add to that list of six priorities or drop? I think two things. Contested logistics; we debated adding logistics at the time. But again, I didn’t want to throw too many priorities at industry at once, so we worked on that as the seventh unofficial priority. What happened later was, of course, the war in Ukraine, and the Ukrainians have now written the book when it comes to drone operations, drone doctrine, drone tactics, and not just how to employ them, but how to manufacture and update on the battlefield quickly. I think if I were sitting in the seat as Secretary of the Army today, I would prioritize drones, and it’s clear to me that the Army Secretary and Army Chief of Staff have done just that. That makes complete sense to me, because drone warfare will be an important component of future warfare, and it’s going to be something integrated throughout our formations and throughout our ground tactical operations. I completely agree with that. As Secretary of Defense, you made great power competition with China—followed by Russia—the core of the National Defense Strategy, and designated them the primary threat actors. Looking at the world now, where do you think the biggest threats are coming from? I think a major achievement of Trump’s first term was identifying this new era of great power competition, and China and Russia were identified as the top-tier threats, with North Korea and Iran as secondary. Of course, terrorism still loomed out there. I put additional spin on that by designating China as my clear number one over Russia. Over the past five to six years, great power competition has only grown more competitive, dangerous, and ever-present. Why is that? Because again, we saw the first land war since the end of World War Two in Europe, in the middle of Europe, and it’s been marked by not just drones, as we mentioned earlier, but by heavy formations, at least in the initial months of the war, tank on tank, mechanized vehicles, you name it, and still every day it’s ballistic missiles, drones, cruise missiles, impacting the people of Ukraine. So great power competition is here, as a result of various conflicts around the world. With Russia and Ukraine, you see the Chinese supplying the Russians, you see the North Koreans supplying the Russians, and you see the Iranians supplying the Russians. If you look at the Middle East, where Iran is the locus of our focus, as the big player in the region, you see Russia supporting them with arms. Iranians have been trying to purchase advanced fighter jets and air defense systems. That should concern us. When you look at China, you see cooperation between Russia, North Korea, and others. The so-called Bad Boys on that list are working together ever more closely, sharing technology, providing troops to Russia, in the case of North Korea. Who would have thought of that? When I look across the world, to me, there are only two countries that are existential threats to us, and those are China and Russia, because they possess nuclear weapons. Of course, they also have large conventional militaries, so my focus is still on those two in that order. China is certainly the greatest threat we face in this century, no doubt. Your time at Red Cell is quite different from your time in Pentagon leadership and at major defense contractors. What advice do you have for founders at Red Cell based on your experience? How has your combined experience throughout your career informed how you try to help incubate and launch startups? First of all, it’s been a real treat to be with Red Cell, my partners on the board, and the firm. The founder, Grant Verstandig, has been tremendous. He likes to point out that I may be the most senior defense official ever to enter the venture world, and there’s probably some truth to that, but I did have an experience somewhat unique among my predecessors, since I came from the defense industry with Raytheon. I knew what it was like working in a prime, and during my years at the Pentagon as Secretary of the Army and Secretary of Defense, I got exposed to this broader ecosystem that includes both the venture community and private equity. I was intrigued by that, and I knew I wanted to go into those spaces after I left office. As we look at companies at Red Cell—where we incubate, bring forth our own ideas, mature them, and grow them—what I look at with founders is, what does the market look like? What’s the total addressable market? What’s their technology, and what is their team? I look at those three things, and the most important among them is the founder—do you have one with the passion, energy, vision, and leadership to bring a team together that can take an idea from nothing to something? To me, it’s about delivering that vision and convincing investors that you can deliver on those items and possess those attributes. To me, that leadership function is the most important. In many ways, that’s no different if you’re talking about a prime. The difference with a prime is that you have large leadership teams, so other members can step in. If a leader is short on some of those qualities, they can be made up for by others on the team. It’s much more of a team sport. When you’re that founder-entrepreneur, it’s you and maybe one, two, or three other people, so you have to be able to juggle a lot of balls. And those are rare individuals. When you’re bringing an idea from nothing to something, what are some capability gaps in the current force and technology space that you’re thinking about most? We focus not just on national security but also on cyber and healthcare. Across the board, we are basically an AI company, with a lot of AI talent, depth, and experience going back years, and we try to leverage that. Whereas some companies play in the software space, some in the hardware space, some in both, most of our efforts, most of our companies are focused on the AI side. We see any number of functions—whether it’s personnel, logistics, Air Mobility—you name it —where we could take back-office systems and really supercharge them with our AI capabilities to make decision-making faster, better, and less costly, and to proliferate them throughout the organization. We’re finding that in any number of areas inside, and I don’t want to give too much away, because we have various ideas percolating, but DEFCON AI is probably the best case right now, where we took air mobility planning, digitized it, and layered AI in there to do scenario-based planning with real-time feeds with regard to weather, enemy actions, adjusted for risk, efficiency, or cost. That’s one technology that’s exportable to the commercial sector, so I think dual-use considerations are a big factor for us as well. You mentioned that cyber is another priority. There’s been this focus on kinetic lethality, and it seems like cyber has taken a bit of a back seat with the downsizing of CISA and other cyber offices in the DoW. Do you think there’s a sufficient focus on cyber given the current threat? I think the cyber threat is ever-present and will always be, because it is an asymmetrical, non-attributable, low-cost way for adversaries—whether it’s big countries like Russia and China, rogue states like Iran and North Korea, or transnational organizations—to attack either our government systems or our private sector systems. I think that threat is always there, always will be, in some ways, in many ways, offense has the advantage. And so, to the degree that Red Cell, our cyber practice, and other companies out there are trying to be on the cutting edge, trying to improve cyber defenses, make them more effective, and help our customers all the better. I don’t see that diminishing any time soon. Where do you see defense innovation going in the next five years? Do you think the hype will last and lead to breakthroughs in more non-traditional companies brought into the fold, or do you think it will fizzle out, with legacy primes remaining dominant? I don’t think it will fizzle out. In fact, I think a nice partnership between some startups and some primes is going to emerge, whereby startups who innovate at light speed and receive a contract that need to scale quickly turn to a prime which has established factory lines, certified workers, and knows how to procure long-lead items and do all those things where they can provide that scaling opportunity for for a startup. I see that emerging as an outcome, and even as I tour the ecosystem right now, some of that’s already emerging. There are a lot of competitors in any technology—drone defenses, drone offenses, solid rocket engines, and so forth—and that’s a great thing for the DoD, because it means you’ll get higher quality and lower cost. But in any situation, there are winners and losers. So the winners will do well. The question is, will the losers kind of just quit DoD and go somewhere else, or will they throw their hat back in on other things? I don’t know, but that’s part of the competition, so I accept that. What would really disappoint me, and we talked about this up front, is if the government can’t reform itself adequately enough to incentivize startups, ventures, entrepreneurs, and founders to stay with DoD and stay engaged in the defense sector. It’s not just the DoD that needs to make these changes. It really begins with Congress changing the appropriations process, avoiding government shutdowns, authorizing National Defense Authorization Acts on time, and a number of other things. That’s my biggest concern: maybe some venture firms will get frustrated, walk away, and go straight to the commercial sector, which would be unfortunate, because there are so many good ideas out there. There’s so much energy. A lot of Silicon Valley and other entrepreneurs are really mission-focused and want to help out the nation’s security and the American warfighter, and that’s a very positive thing.

US can't secure the border alone. Mexico must take a real stand against cartels. | Opinion Mexico and President Claudia Sheinbaum are in a tough position, but the path to success begins when the country decides it will no longer tolerate criminal enterprises. Dr. Mark T. Esper Opinion contributor Nov. 14, 2025 USA Today President Donald Trump has made it clear that the safety and security of the American people are not up for debate. His tough measures to secure the southern border and ongoing military actions against alleged drug traffickers are proof positive of this. The United States is sending a clear signal that it will not tolerate bad behavior in its hemisphere. While some measures are controversial, if not legally dubious, they are part of a broader truth: Regional security demands not only American strength and focus, but also shared action and responsibility by our partners. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum seems to understand that message. Despite sharp rhetoric between our two countries at times, she has cooperated with President Trump. Under her leadership , the Mexican government has extradited key cartel leaders, deployed troops to help secure the border and resisted the temptation to overreact when the White House imposed tariffs on Mexican goods . I agree with President Trump on some issues and disagree with him on others. Border security is one, however, where he is right to apply appropriate pressure. Our southern neighbors must uphold their end of the bargain when it comes to addressing regional threats. Mexico needs to be a stronger partner to ensure border security Partnership is not a one-way street. With U.S. assistance comes Mexican responsibility. Yet goodwill and positive action on some issues will not fix deeper problems. The greater threat lies in Mexico’s inconsistent laws and policies , coupled with widespread corruption and weak enforcement, that fuel cartel power and undermine cross-border cooperation. Mexico cannot fight these criminal organizations with one hand and enable their financing with the other. It makes no sense. Cartels – which traffic everything from drugs and people to weapons and gold – survive in part because they exploit legal and policy gaps, as well as economic distortions, often created by governments. When our southern neighbors’ laws and policies create black markets , cartels fill the void. Mexico’s ban on vaping could be one example. While the United States regulates these legal products, Mexico’s outright prohibition has handed cartels a lucrative smuggling opportunity. This ban has pushed the market underground, forcing consumers who want the products to buy from the cartels, giving them yet another source of income. The same dynamic plays out in the energy sector. Cartels now allegedly move U.S. oil and gas across the border , inserting themselves into Mexico’s legal and illegal fuel markets. Yet the government in Mexico City often looks the other way as criminal groups profit from this illicit trade. One expert who helped Mexico’s treasury calculate the amount of illegal fuel entering the country estimated its value at more than $20 billion . These are not victimless crimes. The revenue from oil theft, not to mention profits earned from human smuggling and the bootlegging of other pharmaceuticals, finances the same cartels that flood our streets with fentanyl and other illicit drugs that kill Americans and hurt communities. US shouldn't expect less from our closest neighbors Regional security around the world has always depended on strong partners who faithfully do their share. In the Middle East , America relies on Israel and friendly Arab governments to help deter Iran and confront terrorists. In Europe , we work with our NATO allies to contain Russia and support Ukraine. In both cases, President Trump has pushed our friends to “do more,” whether that means forcing compromise to rid Gaza of Hamas or pressing the Europeans to spend more on defense. Latin America should be no different. When it comes to trafficking in the Western Hemisphere, Mexico must function as a full partner in the fight against organized crime. Cooperation cannot stop at intelligence sharing or selective arrests and extraditions. It must include coherent economic and regulatory policies that deny cartels the ability to finance their deadly activities. These policies must be vigorously enforced to extinguish corruption. Regional security and prosperity can only flourish when leaders make the hard choices to see them through. President Sheinbaum is in a tough position, no doubt, but the path to success for her country and ours really begins when Mexico decides it will no longer tolerate criminal enterprises that endanger innocent people on both sides of the border. As such, the United States should encourage and assist Mexico while also demanding its full cooperation and tough action. Dr. Mark T. Esper was the United States' 27th secretary of Defense .

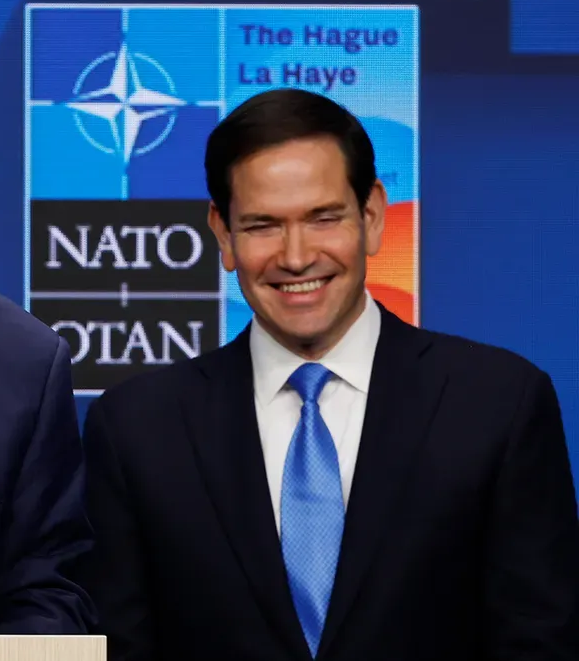

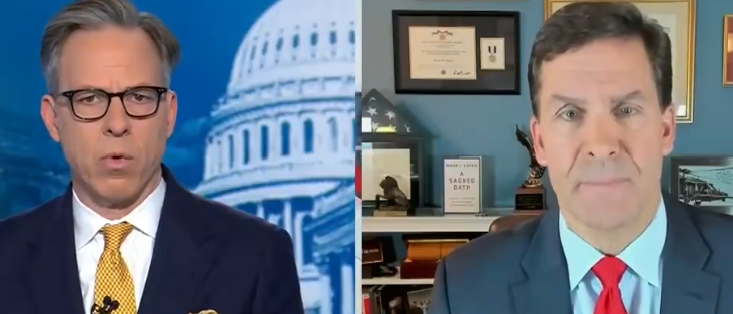

America’s allies are finally paying their fair share for defense. Now they must pay their bills House committee calls out Mexico, Kuwait and other nations for allegedly failing to pay American contractors By Dr. Mark T. Esper Fox News Days ago, President Donald Trump threatened Spain with new tariffs unless Madrid increases its defense spending to 5% of its GDP. Whether this tactic proves effective remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: the president has been even more effective than he was in his first term when it comes to getting other nations to honor their commitments. This fact has been most prominent when it comes to defense spending. In 2006, America’s NATO allies agreed to spend 2% of their GDP on defense. After several years of little progress, the Obama administration secured an updated agreement in 2014 that all would achieve this goal by 2024. Yet when Trump first entered office in 2017, only five of 28 nations had met that mark. The president and his national security team, including me, pressed our allies hard back then to live up to their commitments. By 2021, the number of NATO members doing so had doubled and allied military spending increased considerably. President Donald Trump, alongside Secretary of State Marco Rubio, speaks during a news conference following the NATO Summit on June 25, 2025, in The Hague, Netherlands. On the summit agenda was a new defense investment plan that raised the target for defense spending to 5% of GDP. Fast-forward to 2025. Aided by the ongoing war in Ukraine and a European fear of Vladimir Putin, Trump managed to achieve what many thought impossible: convince our NATO allies to spend a whopping 5% of their GDPs on defense! In the economic space, the White House has similarly persuaded other nations to live up to past obligations when it comes to trade, using tariffs and other means where necessary to do so. This should be more apparent when it comes to future trade talks with China . The communist state has violated its obligations and reneged on numerous agreements for decades, from the theft of intellectual property to currency manipulation and the unfair subsidization of Chinese companies. During Trump’s first term, for example, the PRC notably never purchased the $200 billion in additional U.S. exports it had promised. China may be the most notorious country when it comes to reneging on commitments, but it’s not the only one. Many of America’s friends are also culpable, especially when it comes to deals made with U.S. companies. I have seen this during my own time in the private sector. This is enough of a problem that the House Appropriations Committee recently wrote in the August report of their FY2026 spending bill for national security , Department of State and related programs that it "continues to be concerned by reports of commercial disputes between United States entities and host governments…." The committee noted "particular concern" about "disputes over real property seized, held or expropriated by foreign governments." The report went as far as to call out the governments of the "Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Honduras, Kuwait, and Mexico." Allegedly, Mexico’s state-owned oil company Permex owes American contractors $1.2 billion. Kuwait is purportedly accused of not paying the U.S. for its financial obligations – including for its Al Zour refinery, one of the largest oil refinery projects in the Middle East – where it reportedly has left U.S. and other contractors unpaid. And, per the State Department , many U.S. companies operating in Honduras have "voiced concerns regarding politically motivated threats of criminal prosecution and expropriation of private assets." Secretary of State Marco Rubio speaks to media at Ben Gurion International Airport, as he departs Tel Aviv for Qatar following an official visit, near Lod, Israel, Sept. 16, 2025. (Nathan Howard/Pool Photo via AP) The committee concluded its report by directing Secretary of State Marco Rubio "to utilize the various tools of diplomatic engagement to…. facilitate the timely resolution of such disputes." Such action, of course, begins with America’s diplomats abroad.

The collapse of the brutal Assad regime may not be the last domino to fall in this region. Iran is now the weakest it’s been in decades with the apparent loss of its Syrian client state; the collapse of its Axis of Resistance, especially Hezbollah; and the continued economic, social, and political duress the regime imposes on ordinary Iranians. Might this corrupt theocracy be the next regime to fall? Let’s hope. Watch the Interview Here .

As I noted yesterday, Damascus will fall if Assad flees. This morning it is believed that Assad has left the country and the rebels control the capital. The question now is “who” and “how” will Syria be governed? Right now we should celebrate Assad’s fall and this strategic defeat for Russia and Iran. Watch the Interview Here.